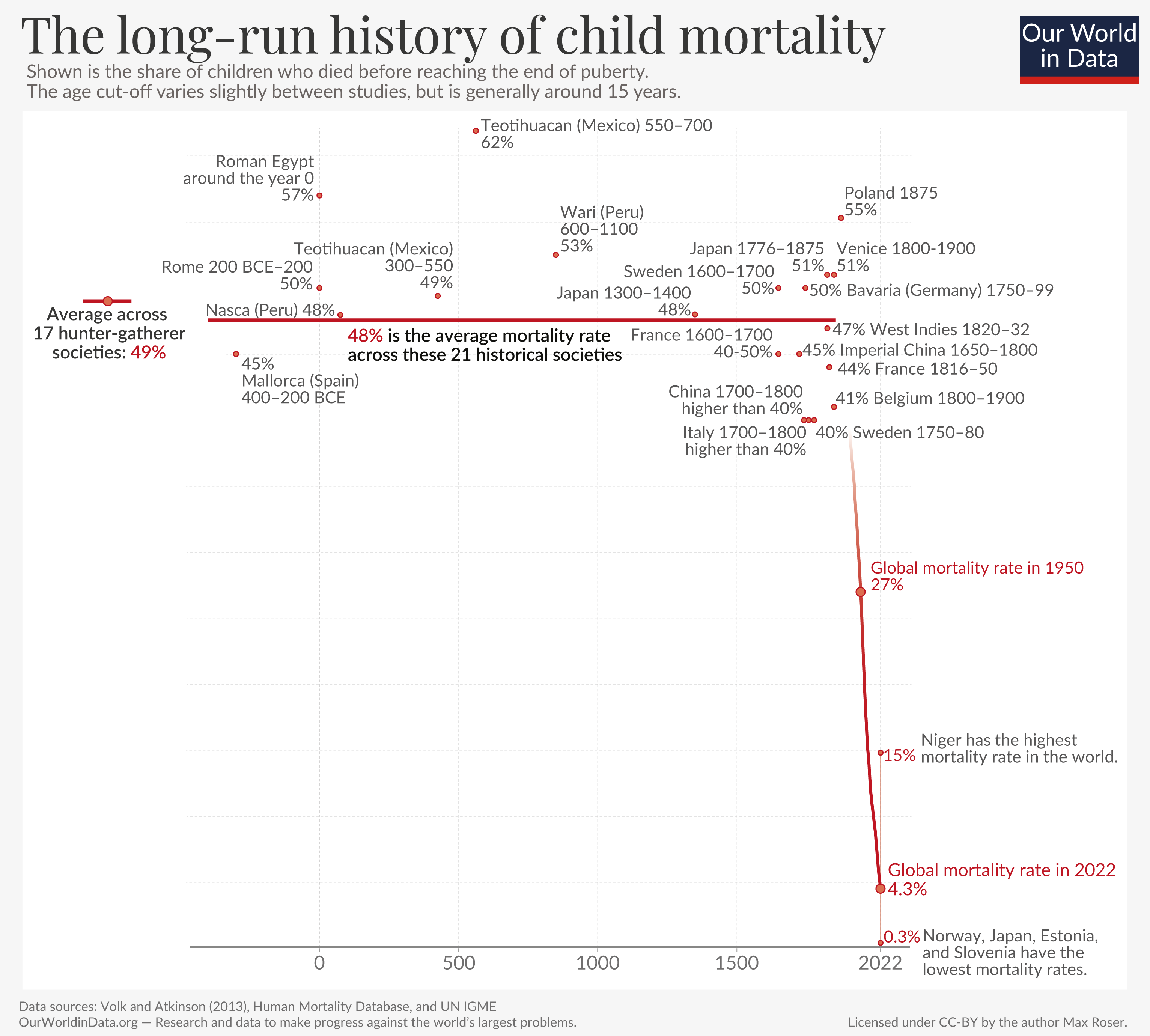

One of the clearest forms of human progress is the reduction in infant and child mortality. But I hadn’t appreciated just how recent, widespread, and fast this progress has been until reading this article from Our World in Data.

Consistently across the world, mortality for children under the age of 15 was 40 to 60% basically up until 1900. Then it dropped to 4.3% globally within 120 years, with roughly half of this drop occurring since 1950.

Consistently across the world, mortality for children under the age of 15 was 40 to 60% basically up until 1900. Then it dropped to 4.3% globally within 120 years, with roughly half of this drop occurring since 1950.

That speed and recency is remarkable. As Max Rosen writes in the article, “Progress can be fast.” The ubiquity of progress is also amazing. For every country on the planet, child mortality has fallen by two-thirds compared to what it was a century ago – and for some countries the reduction is closer to 99%. I would like to have a better understanding of how this achievement has occurred. Sustained economic growth as measured by GDP has been widespread but not ubiquitous. What has worked in the health setting that is failing in the economic setting (or am I simply overstating the difference; the same places that have experienced the smallest improvements in child mortality ?

Seeing this graph, I was also curious about data quality. Of course, Our World in Data has a good discussion of this very issue. And I did take a look at the main source for the graph (Volk and Atkinson 2013), which seemed reasonable at first glance. Knowing how hard it is to track mortality in the present day, however, I maintain some amount of skepticism.

Finally, while writing this, I also happened to re-read Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and encountered David Starkey’s critique that Mantel’s Cromwell shows anachronistically too much emotion at the loss of his child and wife. As many have pointed out, Starkey didn’t read the book, and if he had, he might have been struck – as I was – by how little explicit mention of these losses is given, though it is clear that the character is suffering. More importantly, this view of historical parents as having less concern for their kids seems outdated and frankly bizarre. Our World in Data has an entire page on this. And Medieval Children by Orme provides a detailed account (review and description here).

Version history

2025-09-26: First version

2026-01-23: Typo correction; added thoughts on comparison between GDP growth and mortality change.